By Shirley Kellenson Zinick, as told to Herman and Annette Adelson, November 1982

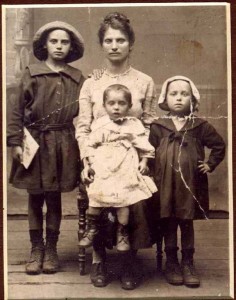

She survived two pogroms and the death of her parents, yet her ordeal was only just beginning. Could the young orphan care for her two young sisters, overcome grinding poverty, and build a life in a new country?

I was born in Felshtin, a small town near the city of Proskurov in the Russian Ukraine. It was a pleasant town with a marketplace, stores, and many comfortable homes.

I lived in my grandfather’s house on a hill. He sold sacks of grain, corn and wheat. He had a cow and sold milk and cream. He also owned an orchard a small distance away. Once I went there and watched the workers pick the fruit. I also remember playing in a brook near the house, splashing in the water with my bare feet. In the cold weather I played with my sisters, Sonya and little Gittel, in the warm loft-like room over a stove.

My father was a tall, slim man who went quietly about his work, making shoes and boots to order for his customers. My mother was also a gentle person.

The Pogrom Comes to Felshtin

My placid existence ended abruptly in 1919. Until then, the Russian Revolution had hardly affected our small town. Then stories spread about the Cossacks, who had been told that the Jews provoked the Revolution. They stormed through the Jewish communities, burning, looting and brutally murdering the defenseless people. They came closer and closer to Felshtin and finally struck in February.

When the news came that the Cossacks were coming, my mother snatched up the baby and Sonya. I didn’t even have time to put shoes on. We slipped and fell down the icy hill, fleeing through the fields and woods, hoping to find a friendly gentile neighbor to hide us. But the peasants, who had been warned that anyone aiding the Jews would also be killed, turned us away.

The Cossacks charged through the woods on horseback and soon found us hiding and grouped us together on a frozen brook. We were sure that they were going to shoot all of us, when one of them, perhaps a Jew himself, said, “Let’s just leave them here. They will freeze to death anyway.”

Later we found out that my grandfather and some of the other elders had paid a group of Cossacks to guard us, but the villains took the money and joined the attack on the town. We struggled back to the house to find the house torn apart by the drunken Cossacks. Many people had been killed. Fortunately, our family was saved.

Life slowly went back to normal, but not for long. During Shavuot, which came about the middle of May, the Cossacks returned. Again our mother snatched us up against the will of her father, who wanted to take my sister, Sonya, his favorite, with him. We fled through the fields and hid in the middle of the cemetery. The caretaker, a Jewish man, found us and took us to his home. When the Cossacks came, he gave them food and whiskey while we hid in a dark corner of a shed.

This time were were no so lucky. When the Cossacks left, driven away by the Bolshevik soldiers, many more people had been murdered, among them my father and grandfather. Those who had been spared gathered up the bodies of their slain loved ones and buried them in a common grave. Even as the bodies of the dead lay in the open grave, a small band of Cossacks galloped by, shooting into the little cluster of mourners.

Somehow we existed without a man in the house, sheltered only by broken walls, sharing what little we had with less fortunate neighbors. During the next winter, news came from the Felshtin Association in America. They had heard of the terrible pogroms and had collected money to bring the survivors to the United States.

Orphanage in Lemberg

We gathered our meager belongings and were hurried over the snowy roads to the nearest railroad station where we were herded onto a train, eventually arriving in Lemburg, Poland, where we would at least be safe from the pogroms that were still sweeping across Russia.

Since there was not enough money to send everybody to America, it was decided that only the orphans would go, so we were separated from our mother. All the children were brought to a synagogue. My mother charged me, “Shaiva, you are the oldest. Take care of your sisters. Stay together.”

At night, in the dark synagogue, huddled with the little ones, I relived the terror of hiding in the cemetery, hearing the yells of the Cossacks as they searched for more victims. At last a rich Jewish woman, who had heard of the orphaned children, came with an open truck and brought us to an orphanage in the city.

Posing as an aunt, our mother visited us. One day our uncle came to tell us that after one of our visits, mother fell or was pushed from the crowded train by a drunken soldier. The doctors amputated her leg, but she died seven weeks later. Now I was the head of the family. How old was I? Seven or eight?

Life in the orphanage was very hard. I tried to say Kaddish for my father and mother. The director of the orphanage, a real Hitler, would not allow us to leave the building. I had made friends with the cook. She left a window open in the kitchen so I could sneak out and go to the synagogue. All went well until the kind people of the congregation gave me a smoked fish to bring back to eat at the orphanage.

I hid the fish at the back of our clothes cupboard, but I couldn’t hide the smell. The director found it, and I was punished. I wouldn’t tell on the kindly cook who had befriended me, but I could no longer go back to the synagogue to pray for the souls of my dear parents.

We were often hungry. Once Sonya got a rusty spoon and wouldn’t eat from it. The director got angry and forced her to eat the mush, even though it made her nauseous. As soon as she went to bed, she threw it all up. We were so afraid that he would punish her again, I took her to the bathroom and washed her and the bedclothes, which we put still wet so he would not find out.

We had to work to keep the place clean. The brass railings on the stairway had to be kept sparkling. We put brushes on our feet and slid around the parquet floors to keep them shining. The unhappy children often quarrelled, and I received my share of bruises in the ensuing fights, sometimes trying to protect my sisters.

At last we heard that our papers had come. We would be able to leave for the United States. We left the orphanage with high hopes, but when we arrived in Warsaw, the ship on which we were booked had already left. We were sent back to the orphanage in Lemberg.

A whole year passed. To a child it seemed an eternity. Again our passage in Warsaw was arranged. This time we were ready, but the ship was not. We waited through the spring. In the summer, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, known to us as HIAS, arranged for us to attend a summer camp in Danzig where we would be close to the ship.

On the first Sunday, all the little girls lined up and marched down the road. My sisters and I marched also, right into the village church. Needless to say, the next Sunday we didn’t get in line.

When the ship was ready, the HIAS representative, a fine young man who was engaged to be married, wanted to adopt my sister, Gittel. I wouldn’t allow it, saying, “My mother left her in my care. We have to stay together.” He was very good to us and when we left for the ship, he gave us presents, dolls, toys, and food.

Voyage to America

It was very stormy. The ship could not dock at the pier. The confusion was terrifying. When we got on to the ferry, I lifted Gittel in my arms and told Sonya to hold onto my skirt. When I got into the cabin, I turned around. Sonya was gone. I called, but no one answered.

“Stay here, Gittel. I must find Sonya.”

I pushed through the crowded cabin, calling, “Sonya, Sonya. Has anyone seen my sister?” No one answered. No one cared. Everyone had their own problems. I had to take care of mine.

I went back to Gittel. “Don’t move from here. There is another cabin at the front of the boat. I will see if she is there.”

I opened the cabin door. There was a blast of wind and rain. I stood against the wall and held onto the door knob. The wet deck pitched up and down. There was no railing to hold onto, only ropes stretched across the heaving deck from one cabin to the other.

I stretched out on my stomach and pulled myself across the open space. When I got into the forward cabin, there was frightened little Sonya, her face smeared with tears. I took the sash of my print dress, put Sonya behind me, and tied the sash around both of us. Out of the cabin into the wind and rain once more, down on my stomach on the rain-soaked deck.

“Hold on tight … not that tight, you’re choking me!” So many years have passed, but it could have been yesterday.

We observed Yom Kippur on the ship. Now we prayed that our lives in America would be easier that what we were leaving behind. The weather was stormy; we were all seaskick. Sonya had a sore on her finger. I was afraid she might be rejected and not allowed into America.

“Don’t cry,” I told them. “If your eyes are red, they may think that you have a sickness. They may send you back to the orphanage.”

We finally reached New York Harbor and Ellis Island. We gathered our possessions into the straw suitcases and waited for our sponsor, our cousin, Gussie Wasserman. She had come to America several years earlier.

Other families were greeting each other with cries of joy. I ran to a couple hopefully, but it wasn’t cousin Gussie. At last she recognized me through a resemblance to my father.

Our suitcases, with the little clothing we had, were stolen. My uncle advertised for our papers, and they were found, but only after we were detained for a week, hoping every day that we would be released.

A New Home

At last we were taken to New York. We stayed with the Wassermans while the relatives decided what to do with us. After all my efforts to keep us together, we were separated. No one had room to take the three of us. Sonya would stay with the Wassermans in the Bronx, Gittel would go to an aunt named Wallowitz on the lower East Side. I would live with my aunt, Dvorah Greenberg.

Aunt Dvorah died tragically during childbirth a year later, and I was sent to live with another cousin, whom I called Aunt Channah Kirchenbaum. There was no bed for me. Every night we would put together two kitchen chairs with the bedclothes on them, and that is where I slept. I was very unhappy there, but tolerated it because I didn’t know where to turn.

I went to Louis Greenberg and asked him to take me to the Wassermans in the Bronx. I had kept in touch with my sisters. The families they lived with adopted them and gave them their family names. Sonya became Sonya Wasserman. We called her “Sunny.” Gittel became Gertrude Wallowitz. I was the only one to keep our family name, Kellenson, but I was no longer called “Bas Shaiva.” Now I was “Shirley.”

I lived in the Wassermans’ apartment in the Bronx and went to school. When I was 15 or 16, the Wassermans decided to move to a smaller apartment. I had to leave school and get a full-time job to pay for a furnished room.

I assembled jewlery for Mr. Duke, who had a small place at 116 Nassau place, not far from New York City Hall. My salary of $15.00 a week didn’t go very far. Every Christmas he raised my pay another dollar or two, but I could never get far enough ahead to afford to take time off to look for a better paying job. I stayed on for 13 years.

Through friends of Sunny I became acquainted with Jack Zinick. He visited me every night and called me at work during the day. After only a week, he insisted on making a ring out of a diamond stick pin and gave it to me.

We were married at the courthouse. When Jack finished converting his sister’s house on 10th Street into a two-family unit, we were married at the synagogue on Eastern Parkway and moved into the new apartment.

My long trip from Felshtin was over. At last I had a home.

© Copyright 1999 by Elissa Leifer